07 Dez Investigations in the “inner foreign country”

Autor: Dr. Wolfgang Hegener

Kategorie: Psychologie

Ausgabe Nr: 81

Dies ist die englische Übersetzung eines ursprünglich auf Deutsch erschienenen Beitrags. Klick hier, um ihn auf Deutsch zu lesen!

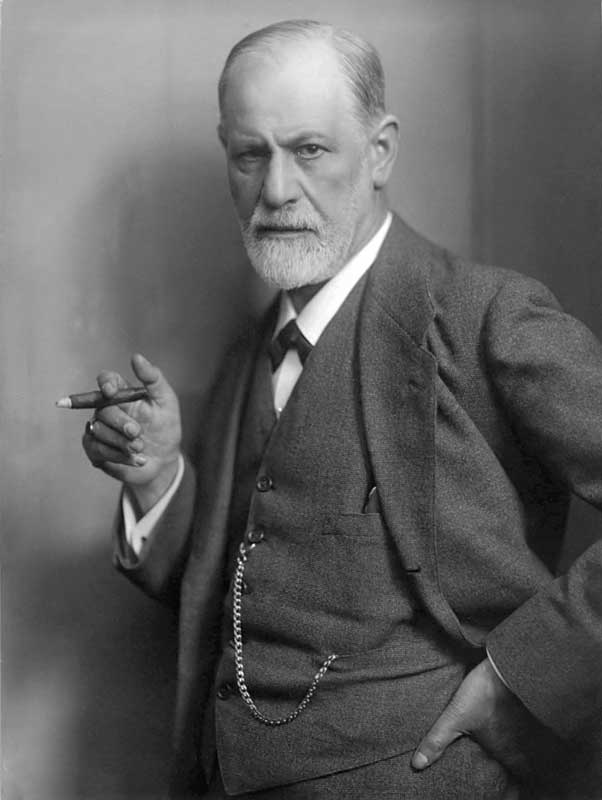

The Freudian Concept of the Unconscious

Sigmund Freud shaped our understanding of the unconscious like no other psychoanalyst. At this non-place within each human being he localized the instinctive, the repressed and the suppressing as well as the various ego instances beyond the conscious ego. Almost 120 years ago, Sigmund Freud (1856-1939) presented his first elaborated psychoanalytical conception of the „unconscious“ in „The Interpretation of Dreams“ (Freud, 1900a). In the following period, the unconscious developed into the central concept of psychoanalysis par excellence.

The history of philosophy is reflected in Freud’s work.

In the developmental phase of psychoanalysis, Freud’s attention was centred on the aspects of the effectiveness and recognisability of the psychically unconscious. In this context, the traditional line of the cognitive unconscious was important to him, but his main focus – and this was his genuine discovery – was on the dynamic or repressive unconscious, which has very different motivational backgrounds (see below). For this reason, he argued, in contrast to Leibniz, that the principle of continuity was not applicable to the actual unconscious. In a mere cognitive view, the Enlightenment remains at the level of the preconscious mind and is all too attached to the model of consciousness.

The two formulations of the psychic apparatus

After these philosophical-historical investigations, it is appropriate that we more closely visualise the role of the unconscious in Freud’s two basic formulations of the psychic structure. In summary, the related theoretical pieces of psychoanalysis are dealt with under the heading of the structural or, as Freud preferred to say, the topological point of view of metapsychology (so Freud called the general theoretical framework of his teaching, which additionally contains a dynamic and an economic point of view). He assumed that in the explanation of all psychological phenomena structures must also be listed, and his thesis is quite general:

the psyche is structured and differentiated into systems.

These systems have circumscribed properties as well as functions and are arranged in a certain order to each other, which allows them to be regarded in meta-theoretical terms as psychological places to which one can give a spatial idea. This assumption, which can only be hinted at here, is rooted in the scientific context of the 19th century, especially in the physiological-anatomical theories of cerebral localisation. Freud, however, in his criticism of these theories – first in his small and exquisite study „Zur Ansicht über Aphasien“ of 1891, in which he dealt with Carl Wernicke (1848-1905), Ludwig Lichtheim (1845-1928) and Theodor Meynert (1833-1892) – emphasised that the instances are something mobile and must be explained energetically-dynamically. Later he emphasised what appears to be very modern, that these psychic places are rather „virtual“ (Freud, 1900a, p. 616) and thus by no means identical with delimited brain regions.

First topological model

As already indicated, Freud has two known topological models. The first conception is based on the subdivision into unconscious, pre-conscious and conscious. Each of these instances has its function, its defensive form, its typical occupation energy and is characterised by its typical content.

The unconscious: This is formed from repressed contents, which are pre-consciously denied access to the system by the process of repression. Its contents are above all desires or, in a later terminology, „representations of drives“, i.e. descendants of instinctive processes that are incompatible and must be suppressed.

It is true that in most writings before the second topic, the unconscious is actually equated with the repressed. Freud also assumes that the unconscious is largely the infantile within us.

The pre-conscious: is dominated by the secondary process (bound energy, logical thinking). It is separated from the unconscious by a censorship, which does not allow the unconscious contents and processes to reach the preconscious without prior transformation or abolition of suppression. Another, further censorship separates them from consciousness.

Consciousness: The consciousness that Freud, unlike all psychology (and large parts of philosophy) before and after him, has strongly relativised, is, so to speak, on the surface of the psychic apparatus and occupies only its smallest part. It stands opposite the systems of the unconscious and the preconscious insofar as there are no traces of memory in it, it is determined by its instantaneous quality of perception: it serves the perception of external and internal stimuli; the formation of memory, on the other hand, takes place primarily in the system unconscious.

Second topological model (structural theory)

Until well into the 1910s, Freud had used the terms unconsciously, pre-consciously and consciously rather in the substantive sense or in the sense of systems. Later, however, he used the terms rather adjectivally, which is directly related to the development of the second topology. From 1923, with the writing „The Ego and the Id“, Freud distinguished between the Ego, the Id, and the Super-Ego. An essential reason for his new conception was that psychoanalysis had turned more and more to the repressive in the course of the development of theory from the repressed, and it became undeniable that unconscious functions, namely the defence mechanisms, are also effective in the ego.

The Id

The Id forms the impulse pole of the personality. Its contents, the psychic expression of its impulses, are unconscious, partly hereditary and innate, partly acquired and repressed. Economically, the Id is Freud’s main reservoir of psychic energy; dynamically, it lies in conflict with the ego and the super ego; genetically, both are descendants of the Id.

Would you also like to learn something about the ego and the superego? You can order the complete article at the bottom of the page.

Paradoxical Constitution – the Unconscious as an „Abroad within“

In the „Neuen Folge der Vorlesungen zur Einführung in die Psychoanalyse“ (Freud, 1933a, p. 62), Freud called the unconscious an „inner foreign country“ with a dazzling formulation. Freud’s formula is truly paradoxical, since its statement describes its own impossibility. How can a foreign country, which by definition lies outside, beyond its own borders, be inside at the same time? In other words, how can a foreign country at home be a foreign country? But precisely this formulation hits the nail on the head of the psychoanalytical understanding of the odd unconscious, as it were, which is neither unambiguously internal nor unambiguously external and thus without a fixed place. It is neither simply something implicit or latent nor a second person or a second consciousness; it is also not a subconsciousness (a term that Freud has always deliberately avoided), i.e. not a psychic background or underworld.

It can be understood more as the articulation and functioning of a difference,

such as that between the latent and the manifest. And further: „The unconscious sends representatives (of imagination and affect), but it is not present as such anywhere. The unconscious does not exist in itself, but only in and through the work of its disfigurement and withdrawal in the intermediate area between inside and outside.

It is only present in its withdrawal and in negation and positive cannot be captured.

If we refer these insights to the previous philosophical lines of influence mentioned at the beginning, we can perhaps say that Freud neither ontologises the unconscious, as it happens in the romantic tradition, nor rationalises it as something (cognitively) merely unknown. Between rationalisation and ontologisation he finds a third possibility that grasps the unconscious as a fundamental dynamic function of the soul and at the same time sets an inescapable boundary for any conscious recognition (cf. also Hegener, 2014, chapter 1).

About the author:

PD Dr. Wolfgang Hegener. Psychoanalyst and Teaching Analyst and Lecturer for Psychoanalytical Cultural Studies at the HU Berlin. Last book publications: „Unzustellbar. Psychoanalytische Studien zu Philosophie, Trieb und Kultur „, „Heilige Texte. Psychoanalyse und talmudisches Judentum “ and „Schuld-Abwehr. Psychoanalytische und kulturwissenschaftliche Studien zum Antisemitismus“.

These are abstracts from the original article.

Only excerpts from the article are reproduced in this version. The complete article in German language, can be ordered in the pdf below.

[wpshopgermany product=“573″ template=“beschreibung.phtml“]

Bildnachweise: © Adobe Photostock

Keine Kommentare