12 Dez The Underworld – The Realm of the Unconscious

Autor: Clemens Zerling

Kategorie: Griechische und Aegyptische Antike

Ausgabe Nr: 81

Dies ist die englische Übersetzung eines ursprünglich auf Deutsch erschienenen Beitrags. Klick hier, um ihn auf Deutsch zu lesen!

A descent into the depths of the soul requires all heroic courage

Already in ancient times, the motive of descending into the underworld is often found, from the Babylonian goddess Ištar to the Greek hero Odysseus to Orpheus, who wanted to bring his beloved back from the deep darkness. But what is the meaning of the underworld, which is also interpreted as the unconscious and the realm of dreams, and what are the mythical figures looking for in this realm? Together with the author, we embark on a journey into darkness, into silence, into the very basis of being.

A descent (katábasis) into the depths of the soul demands all heroic courage.

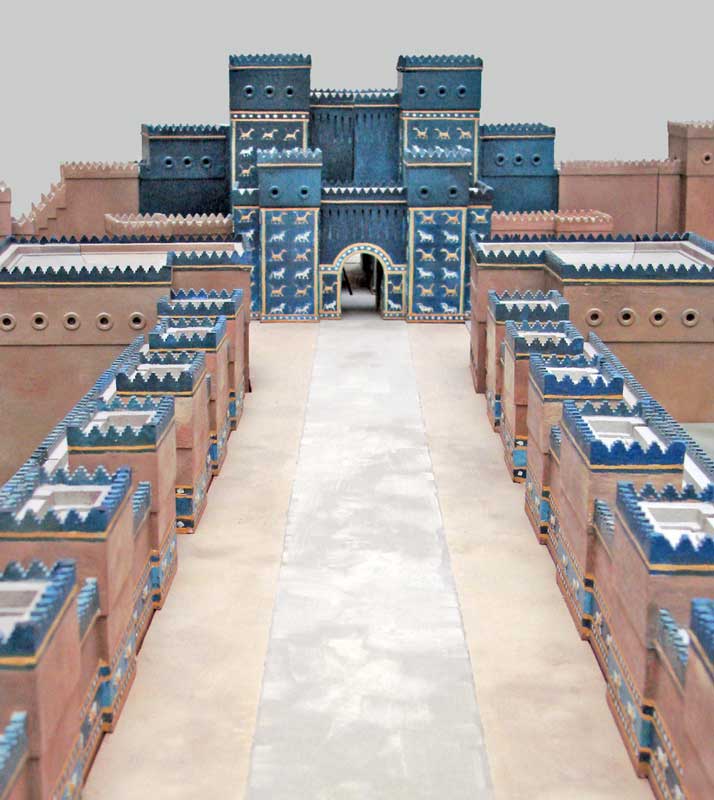

The Babylonian Ištar (presumably = [Venus-]star), goddess of heaven and earth, descends into the underworld, into the “kingdom without return”, full of blind rage, anger and sinister desire for revenge. She, at the same time mistress of all warlike conflicts, wants to incite the numerically superior dead to destroy all living beings on earth. There is no reason for this. But in the underworld only her sister Ereshkigal (= mistress of the great below) rules, and so her gatekeeper Namtar (= fate) refuses access. Burnt with rage, Ištar threatens to smash the gate. Ereshkigal, unpleasantly surprised by this visit, finally agrees to let Ištar enter her kingdom after a fierce debate. But she sets harsh conditions for it. Ištar has to discard one of her insignia as she passed through each of the seven gates: diadem, earrings, necklace, robe needle, belt with birthstones, bracelets and anklets. At the seventh gate she has to take off her robe herself and is completely naked. Finally, completely humiliated by her crouched posture – similar to the dead in Sumerian tombs – Ištar is no longer different from other deceased people. On top of that, the goalkeeper Namtar, on behalf of her sister, has given her sixty illnesses that rob her of every life force. But in her absence, synchronised with her infirmity, all life on earth falters. No seed reaches maturity, humans and animals are unable to mate. The entire upper world is in danger of extinction. Worried, Ereshkigal sends a messenger to Ea, androgynous god of wisdom and water.

Even if “seven gates of transformation” might refer to the declining moon at first, the “passages” suggest stages of a very old female initiation path. Countless threshold and entrance rites in the cultures of mankind testify to the respect for the great feminine in its ambivalent aspect. Now different versions of the descent of the Ištar (Sumerian: Inanna) into the underworld or “hell” have survived, a myth whose oldest Sumerian version goes back at least to the beginning of the 3rd millennium BC. However details vary: It always makes sense for “the wisdom” that Ištar returns to her realm – with her insignia. However, the dark Ereshkigal must first reanimate her bright sister with the water of life. In the younger Babylonian version summarised here, this elixir gushes only directly into the underworld, and only the Mistress of Death has the right of disposal.

The dead are quite close to us.

A Katábasis (descent) led among other things into the realm of the dead, and this really required courage. Finally an encounter with the shadows of the deceased in the “beyond good and evil” was not always easy. Homer’s protagonist of his epic Odyssey descended into this world to obtain information. How could he, Odysseus, find his way back to sunny Ithaca, his homeland island and symbol of the light-hearted homeland of every soul longing for odyssey? Black from decomposition or pale like air formations, the threatening shadows of the departed and ancestors once heeled for fresh blood in order to regain vitality at short notice. Only then they showed themselves possibly ready to reveal searched information. But they were not always well acquainted with the truth.

This article is also available as a complete version in pdf format, where you can find more information about the Katábasis.

The realm of the dead lies in our unconscious.

In dreams and in states of so-called near-death experiences or unexpected openness for the unconscious, the dead can suddenly surprise us. They approach voluntarily, but remain silent: Close family members and ancestors rise from this hereafter to the surface, usually in well-known form, or also unknown. Sometimes they assume urgent expectations: For the indologist and celticologist Heinrich Zimmer († 1943), they basically demonstrate the “continuing, rapturously present face of imperishable life: the night side of its indestructible power, its inexhaustible lust for itself”; “life’s senseless urge to its own survival, in a luringly pompous form or in poor, threatening eeriness” (1987: 270 f.). A (re)identification with ancestors in general integrates the unconscious with its resources and regenerative powers, according to C. G. Jung. It offers a “renewal bath in the source of life, where one is again fish, that is, unconsciously as in sleep, in drunkenness and in death”.

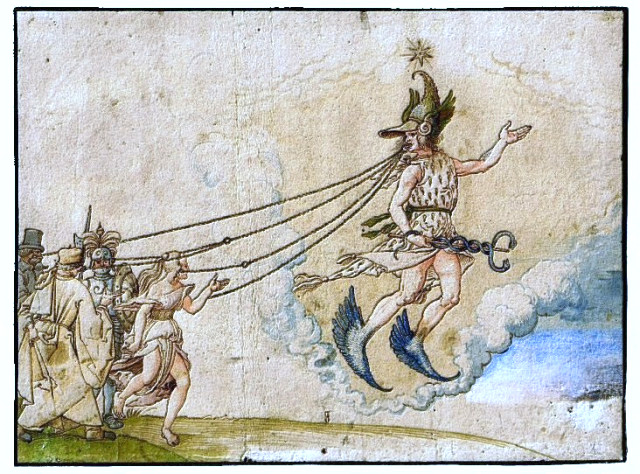

Further information on the realm of the dead can be found in the complete article, which can be ordered as a pdf below.

In the sea of the unconscious, that “hard-to-reach” treasure is hidden. For C. G. Jung, this jewel also described the “eternal companion”. But who is that? Who goes through life next to us and with us? Myths, legends and Holy Scriptures present the motive of a personal and at the same time impersonal companion, who is in the right place at the right time. Since the Middle Ages he has been ghosting through our fairy tales with blurred features in the form of the “faithful Eckhard”. In the Koran the 18th Sura tells of Moses and a strange servant. Islamic exegetes called him al-Chiḍr (= the Green) or Chidher, “son of the water depth”. This helper of Allah represents his opaque, but wise work on earth, pointed in the necessary change. He has drunk several times of the water of life and takes on traits of the ancient soul leader Hermes or of our Higher Self “Green” can here, in the course of spiritual discovery of reality, imagine the last veil of the soul behind which paradise hides. Sometimes Chidher tends to illogical or apparently destructive actions in which, according to Koran, old Moses was embarrassingly entangled. It reflects, among other things, the frequent seduction of man by external appearances.

More about the author:

Clemens Zerling, born 1951, founded his own publishing house in Berlin in 1979 after studying political science with a focus on cultural and religious history, ethnology and hermetic philosophy; active as an author and freelance journalist since 2000; numerous publications in the fields of cult and cultural history, customs and encyclopaedias on symbolism.

Excerpts from the article are reproduced in this version. The complete article can be ordered in German language as a pdf below.

[wpshopgermany product=”570″ template=”beschreibung.phtml”]

Keine Kommentare